Blink and you'll miss it

Social commentary via game mechanics

If we choose to look, it's possible to find details in games that serve as commentary on the ideology of our times, whether intentional by the designers and developers or not. The difference is whether we are open to seeing these details and how we respond.

When things appear as expected, i.e. similar to what we're used to, we tend to not think about them much. They are, after all, a reflection of "how things are". Hence, we often see that complaints about a game being "too political" mostly occur when the politics differ enough from one's values for them to notice. A similar line comes from those who complain a business shouldn't "push" their values on their customers.

Let's not be naive. There is no escaping politics in games, or life, for that matter. One way or another, a game or a product will imply something about something, whether it means to or not. Because a creator is unaware of the statements they have inadvertently made in their art, it doesn't mean the statements aren't there.

The parallels in these games to the current systems of our society often aren't examined, but they do lead us to a few questions.

For example, games set in a historical period often strive for historical accuracy. However, sometimes they focus on the small details to the point that they obsess over what colour dyes people use for what purpose. But, to be fair, researching history can be enjoyable, so who wouldn't want an excuse to do more of it?

Photo by Jeremy Bezanger

Nevertheless, we often take the economic and political elements for granted and flavour history with our modern views of how the world works. So how does pushing our views of the world today onto the past affect our view of history? How does thinking within the current structure prevent our ability to imagine something different or better?

Due to the influential nature of everything we consume, should we be more mindful of the systems we portray? Are we morally obligated to be as aware as possible of our potential influence on others?

I don't know the answers to these questions -- we're looking at individual responsibility within the whole of society. On the one hand, we can argue that individualising the problem won't solve anything. But on the other hand, many find that an authority passing down rules regarding what can and cannot be done is too heavy-handed. Though if the solution is to wait for society to progress to the point that these are petty problems that no one cares about, are we just accepting our generation as lost?

While that may remain a debate for the ages, I still want to look at some interesting manners in which commentary on society and its systems can manifest themselves in games. It sounds pretty formal, but these are mostly shower thought ponderings.

I enjoy all the games I'm about to mention. I've thought about them in this manner because I've spent so much time playing them and have enough familiarity with them that I can switch off a little and think about the real world simultaneously. Will anything I point out stop me from playing these games further? No. Would I recommend these games? Probably, but depends if you like the genres they're from in the first place.

The first game I'll examine shall be Nebuchadnezzar (GOG) -- an Impressions-like city-builder I've been enjoying a great deal recently. Perhaps the fact that I've found it interesting in such a manner is an indication of the state of the games I've been playing lately, but there were a couple of things that caught my attention.

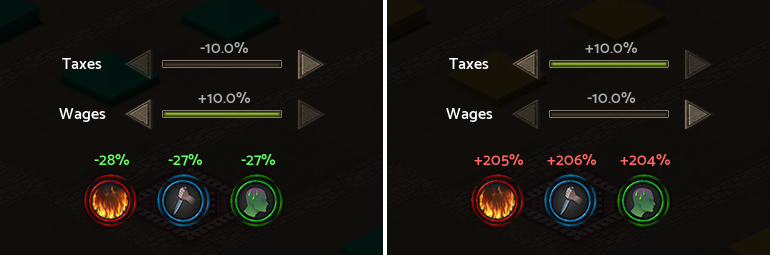

In Nebuchadnezzar, there are three types of risks: taxes, crime, and disease. Taxes and wages directly affect all three - the lower the taxes and higher the wagers, the lower the increase of the risks. These reductions make sense, as those who have very little money left over to cover their needs are more likely to neglect - or rather, are forced to neglect - their quarters and health.

However, the game doesn't warn about crime risk until the city has its first villas - the type of housing required for townsfolk. This is interesting because it implies that state-run police protection - in this case, a city watch - isn't needed until the people become segregated into social classes.

When we only had peasants, the people were provided what they needed to survive or were not, and they were all equal. However, once we introduce a hierarchy of classes, some are born with more than others. In this case, the townsfolk are born into a position higher on the social ladder than the peasants. The townsfolk's additional wealth and privilege are not according to their needs but their station in life.

Furthermore, the workers required for the city watch come from the townsfolk class, making the hierarchy even more explicit. As though it weren't already apparent from our subservience to one with higher standing, ruling over a city whose population consists of multiple classes, each with its own neat, confined place in society.

On the other hand, the mechanics imply that patrols are what reduce risks. Given the inspiration for the game - the Impressions city-builders - not doing so wouldn't keep within the "walker" spirit. However, it's interesting that the opposite is closer to the truth in real life regarding crime.

A similar phenomenon occurs in a lot of games. For example, in Cities: Skylines, we solve many problems by plopping down more service buildings. Any lacking in education, fire safety, health, and crime is easily solved by adding more facilities and increasing the budget to ensure high coverage and capacity. It's a simplification so the player doesn't get bogged down in micromanagement. Still, it would be interesting to have more specific policies than we currently have in the next generation of modern city builders.

Another thing I find interesting with a similar genre, the base-builder, is that even when they don't blatantly use a universal currency, they inadvertently use one. For example, in Dwarf Fortress and Endzone: A World Apart (GOG), we don't have a currency we collect for the purposes of exchange. However, when we trade, we must still match the value of one side's goods to the other. Therefore, we are collecting goods for exchange instead, and each of those goods has a value. So, functionally, we have a universal currency.

There's usually a bit of wiggle room that influences our reputation with the other party, sometimes leading us to give a little extra in exchange for the possibility of a good outcome later or to get something we really need but can't fully afford. Although, in the case of Dwarf Fortress, we could easily just kill the traders and steal all their belongings, but that's another story. Nevertheless, there's no concept of actual debt that allows one side to take something with the promise of returning something later, which might be an intriguing concept to explore in a game.

Speaking of debt, Debt: The First 5000 Years (Book Depository | Booktopia) by anthropologist David Graeber is an excellent introduction to questioning the obvious, for surely one has to pay one's debts? It's not a short book, but the journey it takes is worthwhile, through human history, our economies, and how our perceptions of right and wrong have grown around the concept of debt.

To get away from city- and base-builders for a moment, another game that I had some shower thoughts while playing was Cyberpunk 2077 (GOG). While I thoroughly enjoy the cyberpunk genre, partly because I'm a little bit of a tech nerd, I also find that it isn't the best for many games, despite having a lot of potential for social commentary.

Firstly, what is cyberpunk? It's a subgenre of science fiction featuring dystopian futuristic settings, composed of two terms: "cyber" and "punk". The "cyber" part relates to cybernetics, implying a future where industrial and political coalitions are regulated through information networks and where machine augmentations, drugs and biological engineering are standard. The "punk" part comes from rock'n'roll, referring to youthful, streetwise, antagonistic, alienated individuals that are generally objectionable to the establishment. The juxtaposition of low-life and high-tech often results in conflicts that cause a breakdown or radical change in the social order, thus providing the staging ground for cyberpunk stories.

Given that, we can see where the potential for commentary might arise. But when it applies it to games, mainly those in which we play a singular character, it loses a big part of its critique due to how most games work. The main problem here is that the player character is "meant" to progress and ultimately succeed in one way or another. So while the people working on the game might put in a lot of effort to create environments, characters, and stories that explore these issues, it's difficult to really allow the character to experience the hopelessness of the situation.

On the one hand, this makes sense because it seems pointless to tell a story about someone who has failed to make a substantial change or get anywhere. Furthermore, it doesn't feel good for the player to put a lot of effort into completing a game only to find that our character doesn't at least get a bittersweet ending. I believe these examples are both problems themselves, mainly because games are products. The industry has created a precedent that the player should be able to experience all the content because it is a paid product, so the idea is that the player has paid for all the content. It has also created a precedent where the player often expects to feel personally satisfied by the ending rather than accepting it as the creator's intended experience.

Those issues aside, the overall social commentary problem is more evident in Cyberpunk 2077 than in some other games. This is because our journey is one in which we're kicked to rock bottom and make our way up to become a threat against a massive organisation. So if we die in Cyberpunk 2077, that death doesn't become part of the story -- we reload to an earlier state and try again until we get it right. Our success isn't a question of "if" but "when".

In general, there are hardships and some horrific things that happen along the way, and I can't say more than that without spoiling the story. But nothing that really stops us, and we know this from the beginning, consciously or not, because it's a single-player game with a generally linear narrative. There's no peeling away progressively at the layers of the illusion presented to the populace. There are some neat little details we can stumble upon, but the commentary and impact are generally lost behind the action. And there's a lot of action.

Speaking of action, the amount of crime involving firearms we encounter while simply exploring the city is quite staggering. It clearly indicates that society isn't in a great place, but sometimes it's hard to remember that we're not playing an FPS. While some options exist to sneak around or otherwise avoid a fight, most situations force us into one. So at times, it feels as though the game can lack a little subtlety that other titles, such as the original Deus Ex, can capture.

There's definitely more I'd like to ponder about in the future in a manner similar to this. But I've already rambled and dipped my toes into many different topics. So, I'll leave it here and return with more game-related shower thoughts in the future. Or perhaps I'll find some inspiration to delve deeper into some of the ones mentioned here. We'll see.

---

Screenshots from the games mentioned.